The Importance of Accepting Lived-In Spaces

Author: Oliver Jones

Sustainability is overwhelmingly associated with the environment. We can see the logic behind this association. When considering one of the most pressing sustainability-related issues, climate change, the immediate physical impacts on the Earth like sea-level rise and decreased albedo (reflectivity of the surface) are the most obvious.

If we’re only considering the environment without social and economic dimensions, however, we aren’t seeing the big picture.

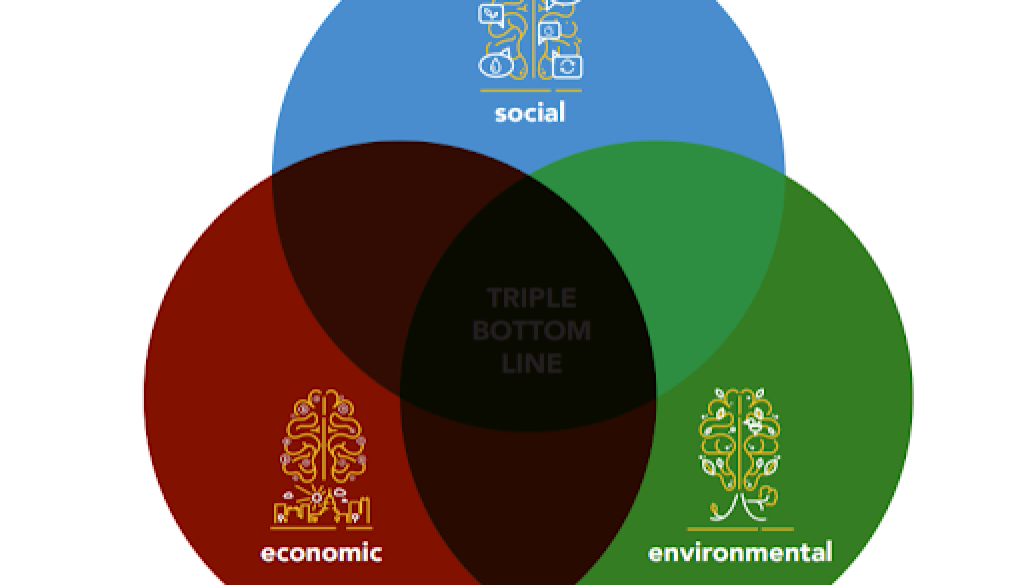

The typical Triple Bottom Line for Sustainability (as seen below) outlines three domains: environmental, economic, and social. These three domains are not exclusive, often overlapping, and the Venn diagram design emphasizes the importance of addressing all three dimensions of sustainability.

A majority of sustainability-related issues require systems thinking, where the complex interactions between the three domains are acknowledged and the world is seen through a dynamic lens.

This is an ideal, of course- prioritization can happen, especially when a pressing issue seems to fall more into one category than the others. Trouble arises when this ‘favoring’ of one domain leads to a neglect of or difficulty seeing issues in a different domain. Oftentimes in practice, this means a prioritization of environmental sustainability and neglect of social sustainability. Examples of this type of bias can be seen in a variety of environmentalist philosophies.

Let’s begin with a school of thought that many of you may have heard of: deep ecology. Deep ecologists are not inherently opposed to economic or social equity by their creed, in contrast to some more insidious brands of environmentalism. Certain ideas that have risen from the philosophical discipline, however, indicate a lack of consideration for social influence on current environmental issues.

The deep ecology movement emerged from the new forms of ecological mindfulness of the 1960’s and 70’s. Deep ecologists reject the concept of ‘anthropocentrism’, and place humans in equal value to the rest of nature. They call for a radical change in the way humans interact with the environment by shifting environmentally, economically, and socially to ‘ecocentric’ goals.

On the surface, these principles seem relatively sound, and indeed they pinpoint some important tensions between thinking of humans as separate from nature and valuing our environment through utility. However, as we see in the case of David Foreman of Earth First, undercurrents of misanthropy can easily become willing ignorance of current social dimensions of power and influence.

David Foreman defines humanity as a “pathological infestation on the Earth”. The fifth principle of deep ecology, listed by Bill Devall & George Sessions in 1985, states that:

“Humans have interfered with nature to a critical level already, and interference is worsening.”

Despite the difference in wording, the characterization of humanity as a monolith is clear. Huge differences in consumption patterns and environmental impact between different nations, populations, and individuals are grouped together under “humanity”.

Typically, environmental philosophies like deep ecology run into problems due to a bias in thinking, not an outright rejection of social equity. Many deep ecologists have a passion for social justice without it running into conflict with their environmental views. The danger in misanthropy, though, is the possibility for apathy towards – or even adoption of – ideas originating from far-right ecofascism.

As the impact of climate change (and the general state of crisis) becomes harder to deny, we are beginning to see a resurgence in eco-fascist ideas. Echoes of eco-fascism can be heard in statements like “COVID-19 is the earth’s way to heal itself” – the implication being that mass loss of life, often disproportionately impacting marginalized communities, is ‘worth it’ for the restoration of the ecosystem.

Eco-fascists place value on a ‘pure’ environmental and social sphere. This usually means placing the blame for environmental degradation on people they see as ‘degrading’ the social sphere as well – people of color, immigrants, and LGBTQ people. Immigration, overpopulation, and over-industrialization are common fears of eco-fascists, and the solution is typically the same: get rid of the ‘impure’.

Even distanced from eco-fascist principles, logics of purity can very easily creep into discussions of environmental sustainability. If we label spaces humans live as “impure” and past saving, then we may miss out on the interconnectedness of the landscape. Wanting to preserve nature, untouched, can lead to little regard for what William Cronon calls the “tree planted in our own backyard”.

This may be, in part, due to the history of environmentalism in the United States. The environmental revolution of the 60’s and 70’s has its roots in conservation movements, which in turn grew out of imperialism and a drive to ‘conquer’ the wilderness. Though environmental movements have certainly changed – I wouldn’t consider many current environmental activists in perfect agreement with Roosevelt – it remains important to acknowledge our historical influences.

Even in the extreme case of prioritization of the environment over human life and autonomy – or, more accurately, certain groups of humans – can be seen throughout history. Infamous figures that could be considered proponents of this set of ethics range from Savitri Devi (a proponent of both esoteric Nazism and deep ecology) to Ted Kaczynski (yes, the Unabomber).

How do we push back against these notions of environmentalism without social equity, then?

The answer to this question depends in part on an exploration of your own environmental ethic – figure out what the things that you value about sustainability are, and question why you perceive them that way.

In addition, expand your political and cultural consciousness by reading and listening to diverse voices. There are disciplines that directly integrate social facets into environmentalism that may help with – here are a few examples:

Political ecology: This discipline looks at political, economic, and social factors in environmental issues. Instead of viewing the environment as an apolitical place, it acknowledges the influence of power relations between humans and the interrelation of nature and society.

Common assumptions in the field of political ecology are that costs & benefits of environmental change are distributed unequally, political power plays an important role in these inequalities, and existing social & economic inequalities are exacerbated by environmental change.

Ecofeminism: Emerging in the 1970’s alongside second-wave feminism, ecofeminism sees the relationships between humans and nature through the lens of feminism, drawing parallels between the oppression of women and the devaluation of nature.

There are different branches of ecofeminism, ranging from spiritual (ex: drawing on Wiccan worship of Gaia) to materialist (ex: liberation of women exploited in the textile production industry by establishing a more sustainable economic system).

Eco-womanism: This could be considered a subset of ecofeminism with a greater emphasis on how environmental issues disproportionately impact women, people of color, the lower class, and other marginalized groups.

The term ‘womanism’ was created to address the inseparable impacts of racism and sexism on black women and identifies culture not as an element of femininity (as intersectionality typically does), but as the lens through which femininity is understood.

Queer ecology: Refers to an interpretation of the environment and relationships between man and nature through a queer studies lens. Often this discipline addresses institutional dichotomies placed on nature such as “natural vs. unnatural” and “pure vs. impure”, and calls for an acknowledgment of the diversity and interconnection of the natural world.